Six days before she made the ultimate sacrifice while evacuating refugees at Kabul airport in Afghanistan, US Marine Corps Sergeant Nicole L. Gee, 23, of Sacramento, California, posted a photo on her Instagram: she held an infant child with the caption, “I love my job.”

Gee was one of thirteen US servicemembers killed in action by an ISIS-K suicide bomber last Thursday, Aug. 26, as the American campaign in Afghanistan came to a bitter end. It was the deadliest day for US troops since 2011.

Background

Two decades earlier, in late 2001, coalition forces led by the US invaded Afghanistan in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, launching what President George W. Bush called “the war on terror.”

US-led forces toppled the terrorist-backed Taliban regime, established a democratic government, and rapidly occupied the nation. Known officially as Operation Enduring Freedom, the Afghan war stretched across four presidencies and has been at the forefront of widespread debate and discussion.

When President Joe Biden was sworn into office in January, he vowed to bring the troops home, a decision that garnered support from both sides of the aisle. More than 2,400 American service members lost their lives in Afghanistan, while civilian casualties number into the hundreds of thousands.

Two decades of fighting cost the United States approximately $2.26 trillion, and because the US borrowed most of the money, generations of Americans will be burdened by the cost. But the cause of the current situation in Afghanistan is far more complex than an invasion and a simple retreat.

In April, US forces gradually departed from the country, abandoning their bases and evacuating soldiers and civilians. Emboldened by the withdrawal, the Taliban launched an offensive, gradually gaining territory throughout the summer.

But after Aug. 6, their advances accelerated with alarming momentum. The speed and size of the assault caught US and Afghan forces off guard. General Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, had estimated that following the US withdrawal, Afghanistan could fall to the Taliban in a period of weeks, months, or even years.

The Taliban swept across the country, capturing province after province and taking several major cities, meeting little resistance. Fearing for his life, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani fled the country along with other government leaders while the Afghan army floundered in the face of the enemy.

A 20-year campaign evaporated in 10 days with the Taliban capturing Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital, on Aug. 16. The United States, and the world, was stunned. The US was now forced to expedite its evacuation efforts as the situation grew more urgent by the day.

As the Taliban entered the capitol, US forces retained control of the Kabul airport, using it as a final base of operations. Hundreds of thousands of Afghan civilians, Americans, and other foreigners flocked to the airport to seek refuge.

What transpired in the days to come was sheer madness. The desperation shown by some Afghan people was indescribable, as young men clung to the landing gears of transport aircraft during takeoff and fell to their deaths midair.

But amidst the scenes of chaos and disaster, US and coalition forces succeeded in evacuating more than 100,000 Afghan refugees from across the country who had fled the Taliban. Far too many, however, including some American citizens, were left behind.

Nonetheless, even after the suicide bombing that left 13 US servicemen and women dead, President Biden pledged that the evacuation would end on schedule. The war was over, and there was no going back.

On Monday, Aug. 30, Major General Chris Donahue became the final American service member to leave Afghanistan, stepping on board a C-17 cargo plane at Kabul Airport, never to return.

Veterans’ perspectives

As the last US troops boarded aircraft bound for home on Monday afternoon, I sat down and spoke with two veterans of the Afghanistan campaign who spent a combined three years of their lives directly training and advising Afghan military and police forces across the country.

I had researched deep into the topic of why Afghanistan had collapsed so fast, but the further I dug, the less I could comprehend. How could an army of 300,000 strong, trained by the world’s premier fighting force, collapse to an army of insurgents within a matter of days? I needed to speak with veterans who were there.

“The Afghan police would get up every morning, and they wanted to be us,” said Andrew Biggio, who served in Afghanistan from 2011 to 2012 as a sergeant in the US Marine Corps. “They hated the Taliban and wanted to be what we stood for. They wanted to dress like a Marine, act like a Marine, and I saw that. I had faith in these guys.”

Alongside 19 other Marine infantrymen, Biggio was attached to Regimental Combat Team 8, stationed in the Helmand province to advise the local Afghan Highway Police (AHP) in military strategy and law enforcement tactics.

Biggio entered the Marine Corps following the 9/11 attacks and had previously served in Iraq as a member of Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 25th Marines.

“In 8th grade, I watched two people jump out of the South Tower of the World Trade Center on television, and that was it for me,” he said. “I was fixated on getting into the service before the war was over. I really wanted to do my part.”

While in Afghanistan, Biggio was stationed at a base with 70 Afghan police officers. As comrades in arms, US and Afghan forces spent years living, training, fighting, and dying alongside each other.

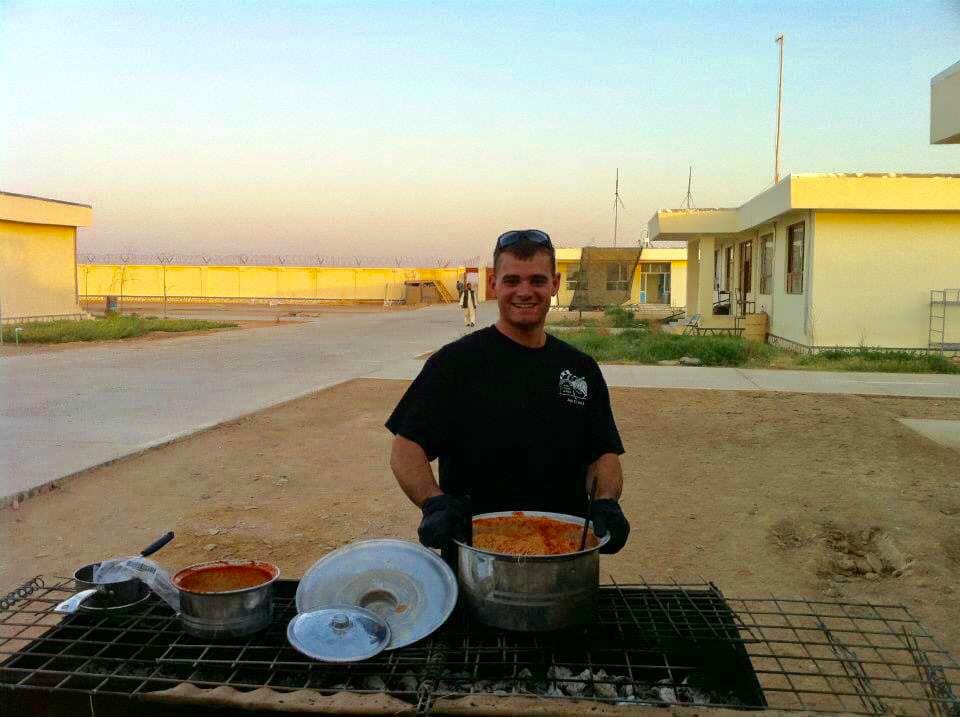

“I ate dinner with them every night,” Biggio said. “I cooked big pasta meals for them, they taught me how to drive a stick shift, they spoke Farsi, and so I learned some Farsi. They respected me, and I respected them.”

Sergeant First Class Sean Ambriz served in a similar role with the 94th Military Police Company, stationed in Afghanistan for two tours, from 2009 to 2010 and 2011 to 2012.

As a driver and combat medic, Ambriz worked closely with Afghan police forces in several villages, areas that were often heavily influenced by the Taliban. But despite the inherent risks and the wounds he personally sustained in combat, Ambriz believes their effort was a noble one.

“I saw a lot of good Afghan people who actually believed in their country and not in the Taliban,” Ambriz said. “They just wanted to see a peaceful life and were doing anything they could to make that happen.”

Biggio and Ambriz are confident that the US adequately prepared the Afghan army to fight independently. However, both were left surprised and confused following the country’s rapid collapse.

“Everyone wanted to see a bit more of a fight,” Ambriz says. “We gave that country everything we possibly could.”

Biggio has a firmer stance on the situation.

“I thought they wanted control of their country,” he said. “At the end of the day, even without 20 years of training and support, all you have to do is shoulder your weapon and fire it for a purpose. I saw the Afghans do that, and I know they had the will to do that. That’s why I’m really confused on why there was no heavy fighting before the fall of the entire country.”

Ambriz believes that it’s hard to say what the future of Afghanistan will look like, especially since the situation is still unfolding by the day.

“I don’t know how historians are going to write about this in textbooks,” he says. “But I do know that as someone who spent two years of their life on the ground there, I have hope.”

Since taking control in Afghanistan, the Taliban have attempted to present themselves as a more moderate group, legitimizing their government, promising to respect women’s rights, and engaging in diplomatic negotiation. They have also pledged to prevent Afghanistan from being used as a base for terror attacks.

But many are skeptical, and rightfully so. It’s important to remember that the Taliban have aided and perpetrated terrorist attacks that wreaked havoc and caused untold grief and suffering across the globe. They were also responsible for harboring Osama Bin Laden, the mastermind behind the 9/11 attacks, which left 2,996 Americans dead.

In addition, when it comes to Afghan soldiers, particularly those who fought alongside US forces as interpreters, the Taliban show no mercy to them or their families. Ambriz stayed in touch with his interpreter “until maybe three or four weeks ago, when he was killed by the Taliban right before the big push on Kabul.”

But perhaps the hardest realization is that multiple generations have fought and died in this war that left Afghanistan with the same regime they started with.

“The Marines killed at Kabul airport last week were nine and ten years old when I was in Afghanistan,” Biggio said. “And that hurts. It hurts to see some kid who may have looked at footage of me in Afghanistan and said, ‘I want to be that guy,’ and so they join the Marine Corps, only to get thrust into this rushed, botched evacuation plan and blown to smithereens.”

“It’s just so sad,” Biggio said. “It ended in the worst possible way.”

Comments are closed.