As a student, I’ve always liked staying a while after class and listening to my professors talk about what they truly care about. Their eyes light up as they talk, and they speak more candidly about their interests than they can in the classroom.

Too often, students are unaware of the academic interests and research that their professors undertake outside their teaching roles. The structure of undergraduate classes means that professors don’t usually have leeway to talk about things that aren’t in the curriculum, or topics that are too niche to expand upon in an intro-level class.

I wanted to create more opportunities for professors to share that work with students in new and meaningful ways. To that end, I conducted an interview with Dr. Lee Lines in the Environmental Studies department where we discussed his illuminating photographic work in the national parks and his efforts to bring the visible impacts of climate change before a wider audience.

As a seasoned environmental researcher, Dr. Lines is no stranger to technical journal articles. Critical climate research is being published all the time, but a vast majority of the literature is composed of technical writing geared toward other trained environmental scientists, making it inaccessible to public understanding. The United Nations Foundation reported in 2021 that U.S. Americans struggle to understand many of the terms frequently used in technical writing about climate change.

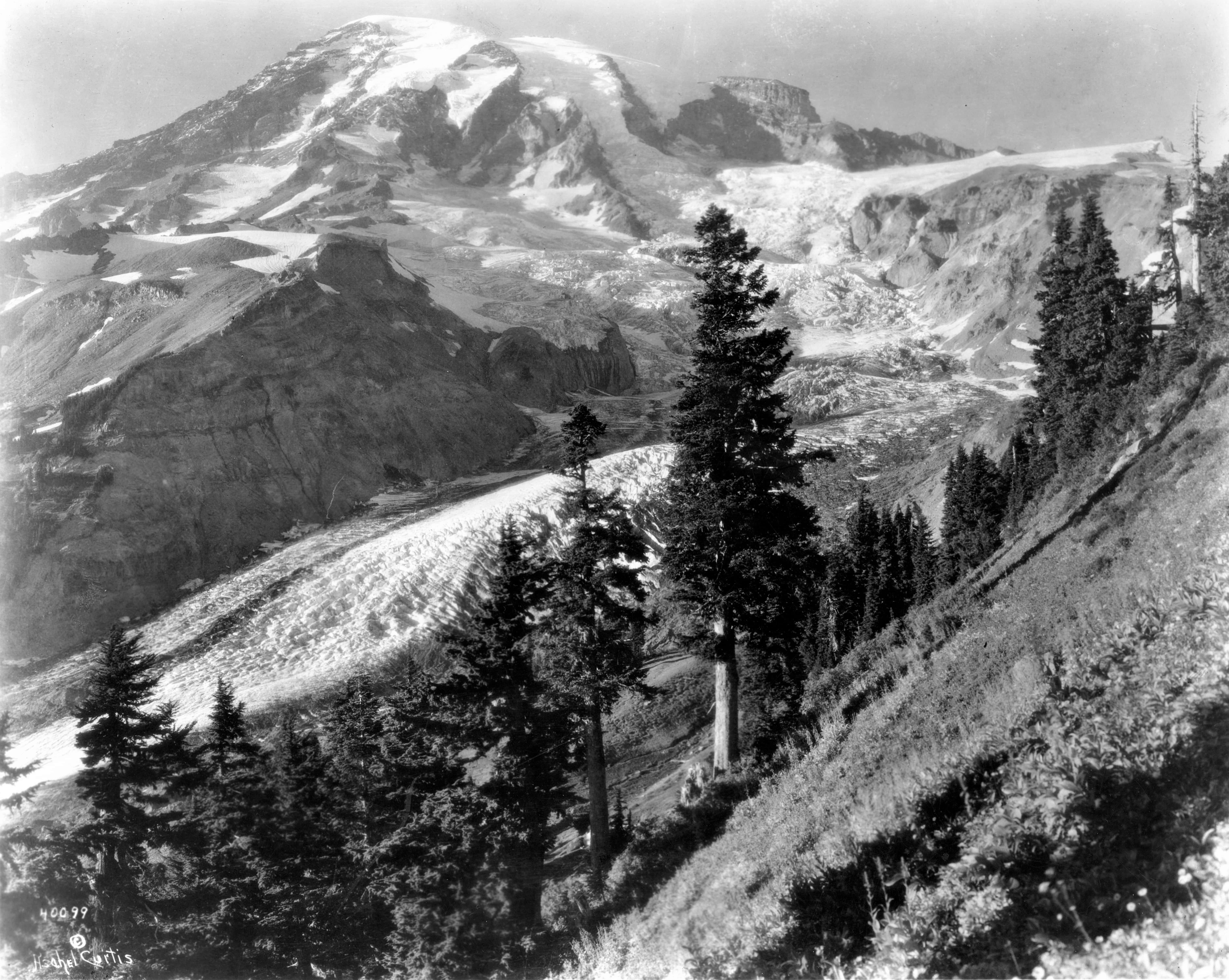

To help bridge the gap between the scientists and the people, Dr. Lines selected a few national parks and surveyed the published literature on climate change in each one, before picking up his camera and setting off to document those changes through photography.

Because climate change occurs as a gradual, long-term shift, the effects are difficult to recognize for infrequent visitors to the national parks. To better visualize the changes, Dr. Lines utilizes repeat photography, where he shows change over time by comparing new photos to old ones.

Since the start of his research in 2017, the scope of the project has expanded to include not just the effects of climate change on the geography of the parks, but also the impacts of the human infrastructure that allows people to visit the parks. Decisions about infrastructure are guided by the dual mandate laid out by the 1916 Organic Act, which established the national parks. It calls for providing access to the parks for all Americans to enjoy and for preserving the parks as completely as possible for future generations.

“Almost always, those two goals are in some kind of tension,” said Dr. Lines. To pursue visitation means more roads and more people; to pursue preservation means significantly limiting foot traffic. Throw in climate change on top of all that, and the parks’ physical infrastructure issues become even more complicated.

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. “It’s not like there’s just one common set of changes that are occurring across the whole park system,” said Dr. Lines. “Each park is experiencing its own challenges with infrastructure, whether it is climate change related, or the increasing pressure from a lot of visitation.”

Because the parks are so varied in geography and climate, these infrastructure challenges, and thus their solutions, must be unique to each park. One good example can be seen at Flamingo Lodge in the Everglades National Park, completed in October 2023. Built to accommodate the high tourist demand for visiting the Everglades, the new Flamingo Lodge is an eco-hotel expressly designed to resist the intensifying hurricanes borne by the warming seas. Its predecessor was destroyed by the back-to-back Hurricanes Katrina and Wilma, reinforcing the need for climate-resilient infrastructure in the parks. Resting atop 13-foot concrete pillars, the new Flamingo Lodge is built to withstand towering storm surges and hurricanes stronger than ever before. “They moved all the crucial infrastructure off the first floor,” Dr. Lines said. “Now, if there’s a storm surge and it floods, it won’t cause nearly as much damage as [it would have with] the old setup.”

This project is unlike any other research project that Dr. Lines has undertaken. For most of his career, his research output focused solely on journal articles meant for other physical geographers. Reflecting on how he wants to spend his remaining years as a researcher before retirement, Dr. Lines hopes to focus more on reaching a wider audience and contribute to better communicating climate-critical research in his field to the general public, especially in the current political climate.

The issue of climate change has split down party lines, feeding a vicious cycle of climate misinformation and destructive policy decisions. “I’ve spent years watching really good scientific research on climate change get into the policy arena, and [then] elected officials distort it, or misrepresent what scientists have found,” said Dr. Lines. He hopes that by illuminating the visible impacts of climate change on the national parks, climate change can once again become a bipartisan issue.

“Whether you’re conservative or liberal… The hope is that [the national parks] provide some common ground, even though people might drastically disagree on some other issues,” said Dr. Lines.

In pursuit of that hope, Dr. Lines has presented his work in the national parks to audiences from all walks of life, whether that be in our own backyard at the Winter Park Center for Wellness and Wellbeing, or up the coast in Washington, D.C. for the 2024 World Heritage Symposium. His most recent photo essay was published in the Parks Stewardship Forum, an open-access journal that reaches people whose work intersects with the national parks, like park researchers and park superintendents.

Despite all the progress that he’s made, Dr. Lines still feels like he’s only just getting started: “As more people encounter these photographs and these pieces of visual evidence, I hope that it starts to help shift the conversation in various places and makes some of the changes more tangible.” He hopes that his work will encourage people to advocate for the parks’ future by voting accordingly, reaching out to officials, and getting involved in the parks.

When asked if he had any closing thoughts, Dr. Lines’ answer was immediate. “I feel grateful that I’m at a college where there’s a tremendous amount of support for the kind of research and teaching that I want to do,” said Dr. Lines. “One of the great things about being in a place like Rollins is [that] I’ve never felt like I’ve been limited by anything other than my own ideas. Rollins has always been super supportive of taking a chance on a research project. Something that’s maybe more experimental, maybe something where on the front end, you don’t exactly know how it’s going to play out. But you do it anyway, because you’re passionately interested in it.”

Professors who would like to share their research with the Sandspur are encouraged to reach out to sandspur@rollins.edu.

The opinions on this page do not necessarily reflect those of The Sandspur or Rollins College. Have any additional tips or opinions? Send us your response. We want to hear your voice.

This article was edited on Dec. 8 to update the link to the Parks Stewardship Forum.

Comments are closed.