September 17, 1787.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The mid-September air was hot and humid as delegates from twelve of the thirteen states convened at the Pennsylvania State House — now known as Independence Hall — for the final day of the Constitutional Convention.

For almost four months, delegates, including Virginia’s James Madison and New York’s Alexander Hamilton, debated and drafted a new governing document to replace the controversial Articles of Confederation.

The Declaration had set things in motion with its deliverance to King George III, establishing the colonies as an independent nation — if they managed to win the Revolution. Confident enough, the representatives of the Second Continental Congress adopted the Articles of Confederation, the first constitution, which established a “league of friendship” among the now independent states. The Articles of Confederation, however, did not create a strong enough central government to unify the independent states, and so both the treasury and military ran amok — there were at one point thirteen different currencies and thirteen different militaries — and trade was almost impossible to accomplish.

With the fear that the country would fall apart before it really ever got to begin, delegates from all states, with the exception of Rhode Island, met to amend the Articles of Confederation. However, it became evident that amending the document was out of the question and a new form of government was needed if the country was to survive.

Today’s Constitution and the Framework of Principles

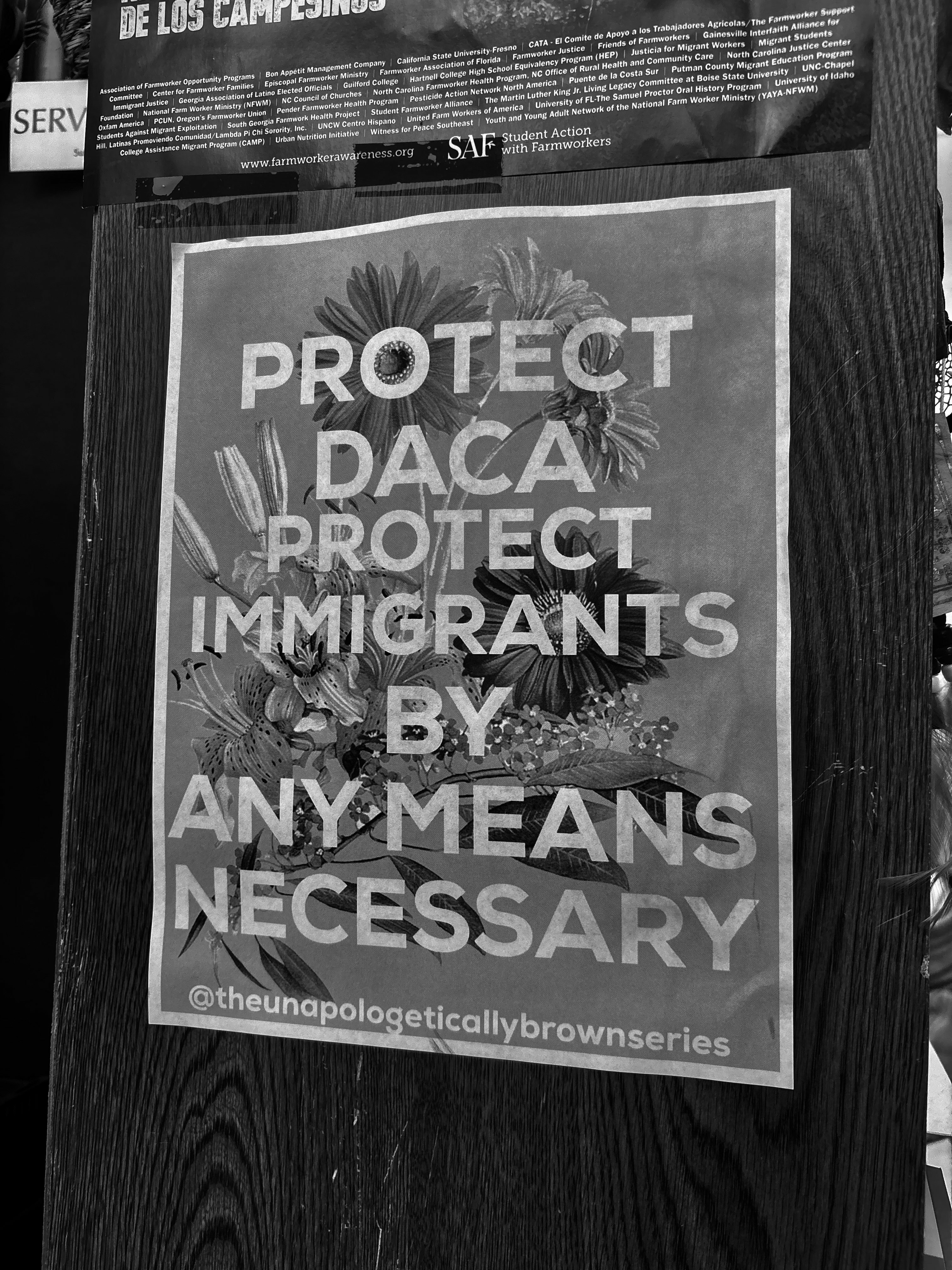

Ten months ago, Donald Trump won the 2024 election to become the forty-seventh president of the United States. In the eight months following his inauguration, how we interpret the Constitution has come into the public eye, the most prominent argument being the protection of civil liberties and power of the executive branch.

The most fundamental worry about the foundation and strength of our Constitution comes from the executive branch. New York Times writer Charlie Savage wrote in a Feb. 2025 article, “In the radical opening weeks of his second term, President Trump has appeared to feel little constraint by any need to show respect for the rule of law.” While executive orders are not illegal by the Constitution, there are multiple lawsuits against orders passed in this year alone, raising questions about the state of checks and balances in today’s society. If the president has the power to do as he pleases, as is the basic case with executive orders, where does that leave the legitimacy of the Constitution?

Inspired by French Enlightenment thinker Baron de Montesquieu, the Constitution divided power between three separate but equal branches of government: legislative, executive, and judicial. This was intended to prevent the government from usurping power from the people and reinstituting the tyrannical leadership that had first led to the drafting of independence. Madison, known to many as the Father of the Constitution, argued in Federalist 51 that “the different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself… It is of great importance in a republic not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers, but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part.”

To further protect the will of the people, with the fear of absolute rule looming over them, the writers of the Constitution included what has now become known as the ‘Supremacy Clause’ in Article Six. The ‘Supremacy Clause’ defined the Constitution as being the supreme law of the land, intending on preventing those in charge from infringing on the rights of the people. This was derived from the concept of rule of law, first introduced by the English in the Magna Carta, that no one, including the government, was above the laws that governed the nation.

If the articles were written to check the government, then the amendments were written to protect the people. The Anti-Federalist camp of the Convention believed that the Constitution gave the national government too much power and wanted it [power] to remain with the states and the people. They refused to ratify the Constitution unless the writers included a Bill of Rights to protect the individual rights of the people.

Forever the subject of American debate since the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798 by President John Adams, the question continues to be raised over how free the First Amendment truly is. From the temporary suspension of “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” to the banning of the Associated Press from the White House press room, among other provocations, the protections of speech and press have come under fire from the current administration. Recently, the question of freedom of religion, or the separation of church and state, has made its way into the headlines of mass media. Over the summer, Texas announced that it would require all public schools to display the Ten Commandments in classrooms, a move that many critics argued went against the country’s value of religious freedom and violates the ‘Supremacy Clause’ of Article Six.

Moreover, the Second Amendment has been at the forefront of debate with questions over whether new gun control measures would potentially infringe on a person’s right to keep and bear arms. The 1999 Columbine High School shooting in Colorado revitalized calls for gun control. President Barack Obama called on Congress to pass a law banning the sale of assault style weaponry in 2016 following the Pulse nightclub shooting, an argument that was strengthened after the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting where lawmakers called on the banning of bump stocks, which allow for semi-automatic guns to be fired as though they were fully automatic. In the week following the Las Vegas shooting, California senator Dianne Fienstein introduced the ‘Automatic Gunfire Prevention Act,’ which would make it illegal to “to accelerate the rate of fire of a semiautomatic rifle but not convert the semiautomatic rifle into a machine gun.”

While each mass shooting reinvigorates the calls for stricter gun control laws, legislators still skirt around the issue, claiming the fear of Second Amendment rights. President Trump was quoted in 2019 in conversation with National Rifle Association (NRA) Chief Executive Wayne LaPierre when discussing the possibility of gun control laws, “And I have to tell you that it is a mental problem. And I’ve said it a hundred times it’s not the gun that pulls the trigger, it’s the people.” Former President Joe Biden signed a law after the 2022 Uvalde school shooting that promoted funding for mental health services and school security and strengthened background checks.

While the Bill of Rights was comprehensive, protecting basic civil liberties — freedoms of speech, press, religion, assembly, and petition under the First Amendment — and introducing due process, it has only evolved in the last 249 years; abolishing slavery, birthright citizenship, women’s suffrage, have only added to the protections of the people by the Constitution.

The Constitution was designed to prevent tyranny, to protect the rights of the people and the states, yet in recent months, the Constitution seems to be failing at the one thing it swore to prevent: the usurpation of power from the people. A modern interpretation of the governing document of the longest running democratic republic in the world reads more like a set of suggestions rather than the backbone of our nation as legislators turn toward personal interest and away from the rights of the people.

The opinions on this page do not necessarily reflect those of The Sandspur or Rollins College. Have any additional tips or opinions? Send us your response. We want to hear your voice.

Comments are closed.