By Heather Borochaner and Zoe Pearson

When Renée Rivera enrolled in Rollins last fall, she was eager to join a college that prides itself on inclusivity and service. However, as a student who uses a wheelchair, navigating the campus’ physical barriers was nearly impossible, making her feel excluded and disregarded.

Participating in off-campus events was impossible, because the college’s buses are not wheelchair accessible. Many buildings she needed to access for events and classes did not have accessible entrances or elevators.

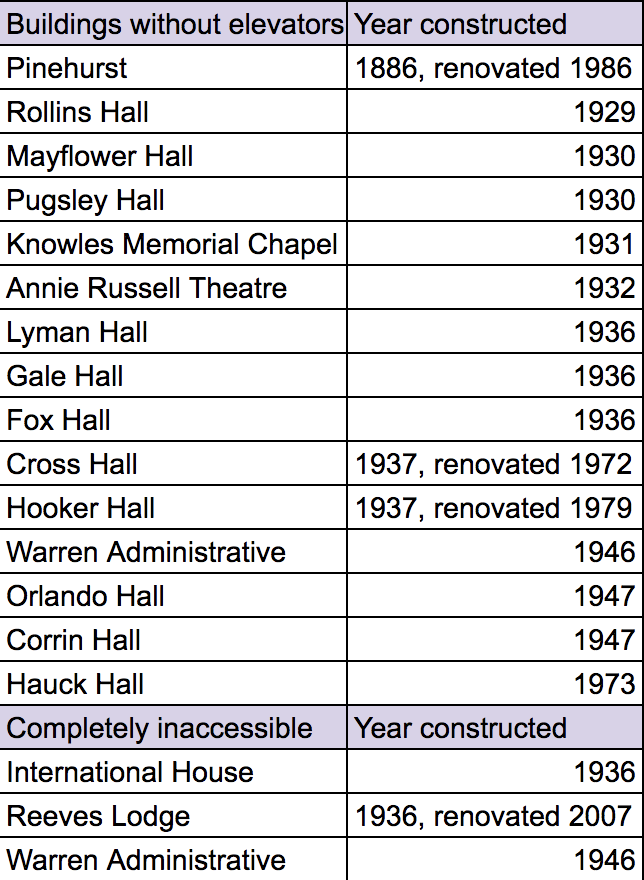

Rivera’s obstacles are widespread on Rollins’ campus. A survey of the campus found that 15 multi-story buildings lack an elevator—only eight of the 19 residence halls have one. It is rare to find a building entrance with push buttons to automatically open doors.

The survey, manually conducted by Sandspur staff last week, counted three buildings that are completely inaccessible, lacking any sort of ramp. Even the Office of Accessibility lacks accessible door knobs.

The difficulty of traversing campus caused Rivera’s chronic pain and mental health to worsen, and her grades suffered as a result. Rivera felt unsupported and after one semester, transferred to the University of Central Florida (UCF).

“I wanted to be able to get my college degree without having to waste my time and energy fighting to do so,” she said.

According to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990, buildings constructed or renovated before 1992—a majority of Rollins’ campus—do not need to be made accessible until it is scheduled for a major renovation.

Yet, even more recently renovated buildings lack essential accessibility aids. While the Rice Family Pavilion, which opened last week after a multi-million dollar renovation, has an elevator and ramp, it does not have a single push button to open its doors.

“I think we are well-aware of the challenges of our campus,” said Whitney Horton, director of accessibility services. “We sit in that tension between we fully agree that the campus needs to be accessible, and the fact that we have these century-old buildings.”

Upholding ethical obligations

Under Title III of the ADA, buildings built before 1992 are required to adjust architectural barriers to improve accessibility as long as it is “readily achievable.” Readily achievable is defined as “easily accomplishable and able to be carried out without much difficulty or expense.” If making a building more accessible impacts a facility’s operation or is very expensive, the institution may not be required to make changes.

Meghan Harte Weyant, dean of students, said that meeting ADA requirements are really the “bare minimum.”

“I wish we could surpass the ADA but we have budget restraints, time constraints, and other obstacles,” said Weyant. “We would love to go back and make our old buildings accessible but it would come at great expense and very time consuming.”

“If students are having issues on campus, they should contact Whitney [Horton] as soon as possible,” Weyant said. “She would work with facilities within a day to figure out how to fix the problem.”

However, the speed of the fix would vary case by case, said Weyant. While installing an elevator is expensive and laborious, changing door knobs to be ADA compliant is low-cost and requires minimal labor.

Still, many door knobs across campus are round, making them non-compliant with ADA standards. This includes those found in the basement of the library, where the Office of Accessibility is located. According to the ADA website, door knobs may not require “tight grasping, pinching, or twisting of the wrist.”

As a student who took exams in the office, Rivera dreaded the pain she would experience trying to get there. “Every time I had to take a test, I dreaded the pain that I knew I would have to deal with just from trying to get out of the room,” Rivera said.

Because there are probably other inaccessible door knobs across campus, Horton and Facilities Services will consider what time is best to change the testing rooms’ door knobs, Horton said. “We want to be sure that work is comprehensive,” she said.

Rivera believes that Rollins should hold itself to a higher standard regardless of legal obligation, and that accessibility should be prioritized over keeping the school’s historical integrity. “The needs of their students should come first,”she said.

Rivera’s initial problems began with SPARC Day, the mandatory day of service all freshmen participate in during orientation at the start of each semester. Her class’ service location was inaccessible due to various level differences at the entrance, which made it impossible for her wheelchair to roll inside.

After consideration, the Center for Inclusion and Campus Involvement eventually moved her class’ location to remain on-campus, but Rivera said the delayed situation never should have happened in the first place. “The entire experience dragged on far too long and made me feel excluded, hurt, and like an inconvenience before the school year even started,” she said. “I was not trying to ‘get out of SPARC Day altogether,’ as one of them claimed,” said Rivera.

When asked about this incident, Weyant said that Rollins’ response was inappropriate. “We need to be committed to identifying issues and coming up with solutions along with working better with incoming students and their issues before they get to campus,” she said.

Weyant feels “deeply regretful” that the experience had that impact on Rivera. “I feel certain that the intention was not to make her feel excluded or not committed to community engagement,” she said. “I understand and I’m sorry.”

“There’s a learning curve and there’s a lack of awareness [of accessibility issues across campus offices],” Horton said.

“But I can say with 100 percent certainty nobody on this campus wants to do anything purposely harmful to a student.”

Communicating the issues

There is currently no formal reporting system for accessibility concerns, but Horton said that the Office of Accessibility Services may add an online reporting form to its website with an option for reporters to remain anonymous.

During the semester before her transfer, Rivera met with Accessibility Services, Center for Leadership and Community Engagement, and other administrators to point out the accessibility problems on campus.

In response, the College will hire a consultant to audit the campus to recommend what Rollins can do to improve its inclusion of students with disabilities. While they are still in the process of hiring, Weyant said it will be complete by the end of the summer.

“[The auditor] will have the expertise from an ADA perspective and from a broader accessibility perspective to give us recommendations on where improvements need to be made,” said Horton.

The College also plans to ask the consultant how to better alert students with disabilities that Rollins has numerous buildings that are inaccessible, wanting to make that information more public.

Weyant suggested either putting a statement on the Rollins website or posting a map marking all of the inaccessible places across campus, but she said they will wait for input from the consultant before taking action.

Starting next fall, students who need accessible classrooms will be marked in an online system to have buildings checked for physical barriers to allow the Office of Accessibility to address mobility concerns before students arrive at class.

Horton said that events in inaccessible spaces is a concern that had not been brought to her office’s attention until recently, but is now planning to take steps to ensure that information regarding event accessibility is more readily available.

“One would hope that we’re always thinking about accessibility in our design,” said Weyant. “I think we’re doing a good job of that with our new construction projects.”

Although Rivera was disappointed in her Rollins experience, she said accessibility is much better at UCF. She said nearly every building has a ramp leading up to an entrance and has at least one push button door. Most buildings have multiple elevators in case one breaks down or needs maintenance. She said the bathrooms are all accessible and some stalls even have push buttons.

“All these seemingly simple things definitely make UCF feel like a more inclusive campus than Rollins,” she said.

She hopes that her story will encourage Rollins to increase accessibility on campus so future students like her can be fully part of the experience that she was denied.

[…] COVID-19 setbacks. After concerns were raised about campus accessibility, as previously covered in The Sandspur, Rollins ordered an accessibility audit, which will eventually be available for public […]