Small vials line up the table, each filled with either dead honeybees or their favorite sticky, yellow substance. Strategically placed on the wall above them are rectangular wooden frames filled with old honeycomb.

These are just two pieces of Zinnia’s Upson’s (‘19) artwork, who, through old materials from bee farmers, is painting a dark picture of the fate of America’s declining honeybee population, all while inspiring viewers to take action to save them.

Between 2016 and 2017, a third of the nation’s honeybee colonies were lost, according to an annual survey of nearly 5,000 beekeepers. This phenomenon is called Colony Collapse Disorder, which occurs when the majority of worker bees in a colony disappear and leave behind their queen and remaining immature bees, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

The honeybee decline will severely effect our nation’s food production, as honeybees are responsible for pollinating about $15 billion worth of U.S. crops each year. Almonds, for instance, are completely reliant on honeybee pollination.

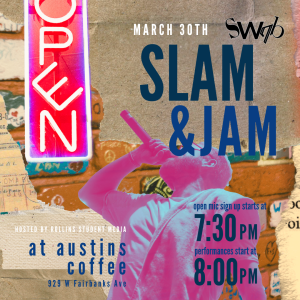

As a self-described foodie, Upson was interested in learning more about the phenomenon and decided to use it as the focal point of her studio art major capstone project. Her work will be featured alongside the five other senior artists in the department’s upcoming exhibition, “Cease & Desist,” which will be in the Cornell Fine Arts Museum from April 12 to May 13.

Upson visited bee farms to collect materials for her project, such as old bee crates and actual dead bees found at the bottom of those crates. She also uses mundane objects such as plates, mirrors, and furniture to create a powerful image.

“I combine found objects with delicate materials such as vellum, twine, and thin wire as a means of referencing the current tenuous state of our ecosystem,” she said. Her pieces give off an industrial feel that closely relates to humanity’s contribution to the collapse.

In one of Upson’s pieces, a dead bee sits on an old-fashioned floral plate with a fork and knife on each side and a mirror that faces the viewer. This shows how the bee decline affects our food industry and how people need to “look in the mirror” to establish change.

“These works focus on the human responsibility to be urgent in responding to the decline of bee populations by accentuating their fragility in relation to our own self-indulgent lifestyles, and how quickly both can change,” Upson said.

By not focusing on a specific cause, she is able to work with the ambiguity of the colony collapse and provoke commentary. “Rather than pointing to a singular source, I instead provoke viewers to consider the long-term consequences of colony collapse and what could be lost in the event of a mass extinction of bee populations,” Upson said.

The exact reason for the bee decline is unknown, but researchers believe that it could be due to beekeeping malpractice, such as spraying unreliable sedatives and transporting colonies haphazardly. Large-scale inorganic pesticide contamination on flowers hurts biodiversity and general bee health during pollination. Habitat destruction due to climate change and the formation of monoculture colonies also threaten the species.

“Instead of taking an extreme approach to this dire situation, I purposefully reference the bees within a poetic and whimsical realm to remind us how humble and immeasurably significant they are to our planet, while also provoking viewers to imagine a world without them,” Upson said.

She urges people to make local changes by volunteering, planting bee friendly-plants, using more organic materials when gardening and being aware of the effects Colony Collapse Disorder has on the food industry.

“I think that, because colony collapse disorder is so ambiguous, people think there’s no way to prevent it or that we aren’t the ones at fault. Through my pieces, I’d like to correct that reasoning and show the need for human change before it ruins our food industry,” she said.

The art exhibit opens on Friday, April 12 at 7 p.m. and runs through May 13. For more information on the featured artists, check out The Sandspur’s coverage of the exhibition from last semester.

Be First to Comment